Around 1896, the father of modern archaeology, Flinders Petrie, was excavating an ancient Egyptian graveyard when he discovered a round limestone disk with a segmented coiled snake carved into its surface. He considered it to be a board game and, over the next century, further boards were discovered. Meanwhile, depictions of a coiled serpent game were found in tombs from the Old Kingdom in Egypt and the association was obvious. It's not certain that Petrie's early find represents a board game, but boards of this design were, and there's no other obvious reason for the snake to be cut into segments that look like playing spaces. This small stone gaming disk was buried at least 5300 years ago so it is probably the oldest known game board in the world by some distance, even if it is a model, rather than a board that was played with. The Ashmolean Museum in Oxford have had it on display for decades, although it is in an unremarkable display case with many other objects, rather than being treated as one of the most remarkable gaming artefacts on the planet. [last confirmed on display in December 2024]

This is the Mehen board held at the Petrie Museum, London. It's date is unknown but it is believed to be pre-dynastic and so older than 3000BC. © Flickr/'C-Monster', (CC BY-NC 2.0)

This is the Mehen board held at the Petrie Museum, London. It's date is unknown but it is believed to be pre-dynastic and so older than 3000BC. © Flickr/'C-Monster', (CC BY-NC 2.0)

Research into the game of Mehen for many years was confused by the fact that the archaeological evidence was inconsistent and some of the early reports about boards and tomb reliefs were incorrect and misleading. In 2024, I published a paper that cleared up much of this confusion. It seems that, while boards varied considerably in terms of size and number of playing spaces, they all have a single spiral snake with its head in the middle and its tail at the edge. The Petrie Museum board shown is typical of the 'grooved' form of board while the photo of the board at the British Museum, below, represents another "pitted" style of Mehen board. Some of them have protrusions sticking out from the side - a trapezium shape, the head of a Nile turtle or a goose encircling the board.

The Meaning Behind Mehen, the game

Everything in this era was steeped with religious significance and games were no exception. Mehen was a God in the form of a snake, and a critical one, in ancient Egyptian mythology. Each evening, the sun god Ra, would disappear beyond the Western horizon and would spend the night sailing through the underworld on his magical barque before being reborn in the East for the new day. The journey through the underworld was dangerous and and various hazards and enemies would be encountered so Ra needed help to defend the Barque from attack. Chief among the defenders was Mehen, who surrounded Ra with his coiled body to protect him. Since Ra therefore lay at the centre of Mehen's coils, it seems that ancient Egyptians probably believed that the body of Mehen was like a pathway to reach Ra - if you entered Mehen's body at the tail end, you could travel through it to reach Ra at the centre. The ancient pyramid texts describe Kings and Queens being reborn through the nose of the snake God, Mehen in a blast of fiery breath. Ancient Egyptians spent much energy ensuring that Kings, Queens and members of their inner circle would survive and exist happily in the afterlife, and the board game Mehen seems to be an example of this, since boards, game pieces and pictures of them have only ever been found in graves and tombs. It seems possible that after a person died, Mehen's body was seen as the route by which their spirit or 'Ba' could leave the underworld and join with Ra. From this, it's easy to see how the game of Mehen could have represented this journey, the game pieces being the dead person's soul undertaking a dangerous journey through the body of the snake God to meet Ra. In fact, the games and images of them on walls might be more than just a game; they might have been left in the tomb as critical equipment necessary in reality for the deceased person to reach their goal.

Mehen in the Tomb of Hesy

The beautiful picture of the three games depicted on a wall in the Tomb of Hesy, Saqqara, Egypt. Senet is shown at the top, Men is shown at the bottom and Mehen is in the middle. Believed to have originally been drawn by Annie Quibell, James Quibell's wife, the colours of the marbles have been corrected by the author to match Quibell's report. The picture belies the fact that the wall was in a very poor condition, when discovered, and Quibell could only just make out some of the colours and shapes.

A picture found in the 3rd Dynasty Tomb of Hesy by James Quibell shows three ancient Egyptian games, each with a board and its playing pieces - one of the most important finds in board gaming history. The Ebony Mehen board is shown accompanied by six sets of six small balls (marbles), 3 lion figurines and 3 lioness figurines. A few other tombs have unearthed similar sets of ivory lion figurines together with little red, white and black marbles so this seems to be the main format for the game of Mehen. The lion and lioness figures are quite big, (real ones found typically vary from 5 - 9cm long) and are far too big to be played along the much smaller spaces on the segmented snake track. Most people who've thought about the game believe that it was a race game of some kind and so for Hesy's game, we have to assume that marbles were played along the track.

The Stone Mehen boards

The Mehen board at the British Musuem has a pitted track. The marbles are from a different find, but they show how the board might have been used. © James Masters

The Mehen board at the British Musuem has a pitted track. The marbles are from a different find, but they show how the board might have been used. © James Masters

A few Mehen boards have a pitted track, the design of which would work very nicely to move marbles around but, for most of the stone boards found, it's difficult to see how marbles could have been used because the spaces are raised and any marbles placed in the channels between them would roll around randomly. Perhaps pawn type pieces were moved along the spaces on some of the boards - but there's no evidence of any and some of the spaces on some boards are just too thin to hold a pawn. A second paper published by me in 2024 discusses this subject at length and shows that there is a way that ancient Egyptians might have played marbles along the grooved boards. More evidence is needed, but as things stand, there is no reason to rule it out.

Mehen - How was it played?

Mehen lions and marbles held at The Louvre Museum. © Flickr/kaironinfo-4u (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0). Notice the collars around the necks of the lionesses indicating that they were captive or subordinated.

Mehen lions and marbles held at The Louvre Museum. © Flickr/kaironinfo-4u (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0). Notice the collars around the necks of the lionesses indicating that they were captive or subordinated.

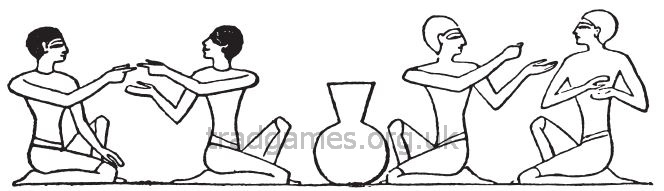

Regardless, it's clear from the tomb of Hesy and some other ancient Egyptian tomb reliefs that somehow marbles and lion pieces were used for playing a game on Mehen boards during the period from 3000BC to 2000BC - so how on earth was it played? In particular, in the tomb of Hesy, dice sticks are shown for the game of Senet but not for Mehen so how did the ancient players know how many places to move their marbles each time? I have shown that the answer is almost certainly that only a few marbles were raced along the serpent track and the rest were used to determine movement using "marble-guessing" rules. One simple way that this might have worked is by one player hiding a number of marbles in their fist. If their opponent guesses the number, the opponent moves a game piece along the track by that amount, otherwise the player holding the marbles move their own piece by that number, instead. The evidence for this is pretty strong - the marbles are just the right size for it, a relief in the Tomb of Kaemankh shows one Mehen player holding up a fist to the other player, another in the Tomb of Idu shows a player holding his palm face upwards towards the opponent and other images show players hiding their hands.

Play at Mehen from the Tomb of Ibi. Although this tomb is from a much later era, the tomb relief is believed to have been copied from a 5th Dynasty tomb of the Old Kingdom, as was fashionable at that time. This means that not everything in the image is necessarily accurate but other images that are from the Old Kingdom show the same positions of a fist held up to the opponent and hands being held back, as if hiding something.

Play at Mehen from the Tomb of Ibi. Although this tomb is from a much later era, the tomb relief is believed to have been copied from a 5th Dynasty tomb of the Old Kingdom, as was fashionable at that time. This means that not everything in the image is necessarily accurate but other images that are from the Old Kingdom show the same positions of a fist held up to the opponent and hands being held back, as if hiding something.

As for the lions and lionesses, we don't know what their role was, but there are a few clues. The lionesses have collars and we know that the ancient pharoahs did capture and keep lions. Perhaps, in the game, one player would own lions, the other lionesses, and they could be sent to attack the other player's pieces. The tomb of Rashepsess show a lion and a lioness both pointing at game pieces between the player's fingers which backs that idea up.

References

My papers on Mehen were published in anonymously peer-reviewed, academic journals:

Mehen, The Ancient Egyptian Serpent Game: A Reappraisal of the Evidence Set, Interdisciplinary Egyptology, A Journal published by the University of Vienna, Austria, September 2024.

Mehen, The Ancient Egyptian Serpent Game: A Reappraisal of Game-Play Theories, Birmingham Egyptology Journal, University of Birmingham, UK, published September 2024.

The Fitzwilliam Museum also published an article on the Mehen board at the Fitzwilliam Museum written by me in conjunction with Dr. Melanie Pitkin.